Having played the campaign X times (more on that later), here is an extended review:

Solo Battletech: …works!

The bad is that you are, ultimately, limited in terms of your own skill and ability to do field analysis. I do not think that playing this will do much to make you a better player. But as a way to play Battletech by yourself, or even with others in the sense that you can do co-op or use the cards for third party forces in a battle, it provides you with a clear framework to use, and a method for deciding what to do that is not merely opinion. Is it always the best move? No, but in the way sort of that you would find with a regular player (and arguably you can always ignore to do something optimal if you want).

What I liked the most about it is that role (Scout, Striker, Juggernaut, etc) is flexible. The deck is not fixed to the type of role that mech has, but represents a different style of play. While there are a non-zero number of ways you can break the game like this, I ended up liking it a lot. It gave verisimilitude in feeling like I was dealing with different sorts of mechwarriors rather than generic mechs.

That there are only two ‘leader’ cards, so it is much harder to judge that part of the system.

The Stuff – Come on now, who actually wants a box of Alpha Strike terrain and second line Clan mechs?

Oh, wait, that’s me.

A Bane-3 and a model bridge at Alpha Strike scale? Sold. Even with the high price tag I felt compensated on this side alone with the miniatures, the terrain, and the tokens.

This does come with a side of problems. The training mission assumes you own the Alpha Strike boxed set based on the minis that are used. That is what the box itself says. All the missions assume you have the terrain from the AS boxed set (or the terrain pack as sold separately), particularly in regards to the buildings. But after that initial go, you never touch the other minis.

The first time the Marauder IIC showed up, I cheered. The 3rd time, it started to grate on me.

There is a logic here. They give you toys, they want you to get to play with them. This way, there is no question that you have all the mechs you need for any given mission. And in a game balance way, your own mechs are able to bounce back, immediately, from most destroyed on the field situations. But, look, it does not feel very Battletech-y.

I like the logistics game a lot, and I like the ‘combat as war’ to use an OSRism. It is one of those points that stands out Battletech from That Other Game. There is a gesture to that with the different sets of rewards, but it feels futile. I may get more points for destroying more mechs. But there is no sense of change, no sense of the slow grind of war.

The Player Force – Overall, the rules for building a mercenary company are good. There are easy and more complex variants, and they allow for a mix of unit types. You have a good sized army to work with, which allows for different task forces or to cover different sorts of approaches. (That may be a bit of play advice. I ordinarily play Alpha Strike with formation rules, or at least building to the different formation types, and coordinate lances. Here I found that diverse lance composition usually came out ahead. Mostly.)

The Named Pilot rules reminded me of 4E: well balanced but bland.

On the good side, the Named Pilot rules create a pair of interesting choices. Named pilots give extra talents in one way or another, but act as a drain on your overall resources. Similarly, the XP system for Named Pilots works by making you choose between improvement in one of three areas. This makes each one of them different, and presents some interesting choices in terms of how to build them up (even if there are a smaller number of optimized routes). And the inclusion of both Battle Armor and Combat Vehicles in the potential categories gives further layering.

But it fails to stir the blood. It feels wrong to complain about a system working too well, but the Named Pilots often end up feeling more generic than the mechs themselves. I am wary about overstating this. It may be that the sort of system that I wanted to see is different. But I found myself more detached from most of my pilots than I like to be in Battletech.

It felt particularly distracting because – well, okay, one of the things is that each sortie has an MVP, who is the Named Pilot who did something memorable and who gets bonus XP for it. About half the time, I wanted to give the MVP to a different, unnamed pilot. (There was one Nova pilot in particular in campaign one who was clutch, who repeatedly pulled off a shot that managed to be the turning point of a sortie.) Again, this comes into the factor of “What Battletech Means to Me,” but that personality of each of pilots and the sort of social milieu that they fit in is something I love about Battletech, and why I like it as a setting and game.

The last bit of the force building rules worth mention is the two discrepancies about force rebuilding.

The first is that forces are vastly different than in the Hinterlands book, operating at a scale beyond what that set of rules uses. It’s not complex math to adjust, but it seems like an own goal making your rules for what amount to the same thing not immediately compatible.

The second is potential errata. The advanced composition instructions have you picking units from the Master Unit List, specifically those available to mercenaries in the ilKhan era. It is what it says it is, though this does sometimes get a little cumbersome, or I was surprised at what was or was not on the list at times.

There is also a purchase list for more units. This is a much more extensive list than in the Hinterlands books for different planets. The rules flag that there are units that are not otherwise available in unit creation. Which is odd in the sense that some of them are. But the confusing (or frustrating) bit is that there are only two combat vehicles; no infantry; no battle armor.

There are a variety of ways that I could read this, but in that narrowest of construction I find it anomalous, that I can buy a Phoenix Hawk IIC but not a Scimitar, much less source a couple guys with a technical.

The Campaign – This I must break into three sections, Powers of Ten style.

The missions – I like the sortie design. We have some classics, like assault or defend a position, along with some more creative ones, the standout in that regard being the ‘no one prepared for this’ fight. The waypoint system adds variability and replayability, and finds different ways to use narrative in the game.

I particularly liked the way that the force composition met with the mission types. It allows for different elements to shine, both within a company and between companies. One instance was a force that had a stand up fight that they got totally mauled in, followed by a more stealth-oriented mission that they positively leveled the enemy.

I am inclined to think that the rewards system, as well as the costs on the bonuses, was balanced. I was never struggling to make sure that I had enough pay, but there were times it was close. However, I also feel like this is something that would take a lot of runs to identify well.

The criticism here is that the layout can be maddening. The maps use a 4X4 grid. While I ended up marking up my table and having some handy yarn, some of the terrain placements I spent more time than I should have trying to get ‘right.’

I have a quibble with the introductory fiction to each sortie, but that leads into the next point.

The Story – I adore the general framework of the story here. It fits well within the themes around the Hinterlands and the era in general. Classic without venturing into cliché.

Early on, FASA realized to keep the fiction of the metaplot a core element of Battletech (and for that matter lucked out taking a chance on Stackpole. I make fun of him a lot for his foibles, but I admire anyone who does seize the moment, who works at it and becomes as solid a writer as he is).

The quibble here is that the mission fiction captures the flavor, but then is not represented in the mission itself. I would think not to remark on this, but mission events do include narrative. So, repeatedly, the instance happened where I would read the fiction, think “oh, cool, Y is going to happen,” only for it to be set dressing.

I do not want to make too much of this complaint. I would not think of it in, say, the Turning Points where it is only ambiance. Instead, it feels like a teaser.

You could call this ludonarrative dissonance. I don’t know if that’s the right term. It is one of those terms like ‘irony’ where the discourse about its misuse is itself misused. If it is, though, then I think that there is a bigger problem of it in the storyline.

In some ways, this is a mirror of the “Same Six Mechs” problem. To explain the general framework: some missions or choices in missions give you a keyword (say, FLORIST). That keyword pops up in other missions, so the instructions might say ‘if you have FLORIST, read A384.’ The reading would change some parameter of the mission.

These are uniformly disappointing.

Okay, not uniformly, but there is all of one instance where I thought it was cool; two, if you consider the elements in the next section. Most of the time, “that’s it?” was the refrain. I understand this from a gameplay perspective. Much like the mechs popping back there is a risk of one side getting overpowered, or it making a mission insufficiently challenging.

It still feels bad. The sci-fi equivalent of killing the giant that guards the soulstriker sword, only to get handed a card with a +2 greatsword on it.

The Superstructure –

The beginning is much better than the ending.

I don’t think that this spoils anything, but this:

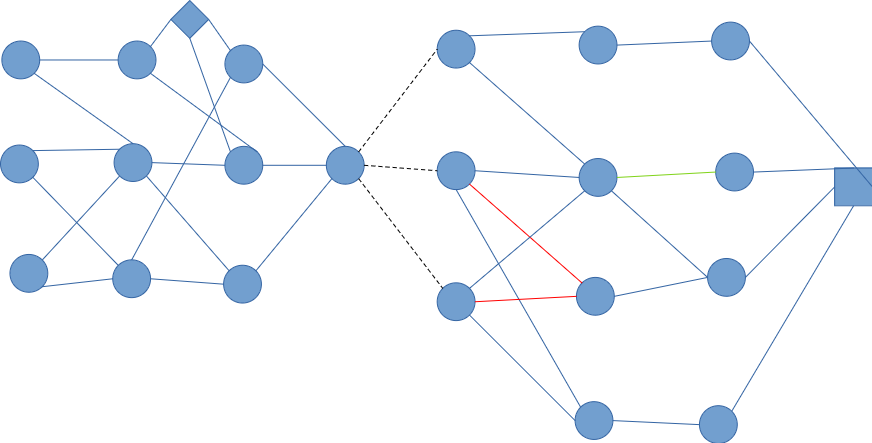

is the architecture of the Scouring Sands campaign. The basic format is that each sortie results in an number of choices, which you then pick to move through the campaign. The missions cannot be failed. If you fail, you try it again. Structurally then, it is a series of choices, that reduce down to a single mission, then become a series of choices again, arriving at a conclusion after the same number of sorties.

(It is a bit besides the point for things, but the diamond represents the exception to the ‘you cannot fail’ state, where if you do not fulfill the assigned task, you still advance, but you do not have a choice in your next mission.)

The red lines are where extra choices exist if you have a certain keyword. The green line is where a keyword changes the resulting next mission. The dashed lines are where the specific victory condition of the mission determines what the next step is. (Someday, I will come back and make this accessible.)

The first half works well. The only oddities appear in replay, where some of the explanations for the premise behind the sortie make less sense when you know the whole mission. The player always has a choice, there are enough choices to make it interesting without so many choices that it becomes unmanageable.

The bottleneck itself is good, or its a clever structural choice that fits within the context of the story. The trouble stars with the yellow lines. The yellow lines track to what is intended, I think, as a sort of win/lose/draw condition from the sortie. Except that the ‘lose’ is the hardest to accomplish, and the ‘win’ is the easiest. Maybe someone has a different experience? If you do, let me know, I’d be fascinated to hear about it.

The bottleneck also has another clue as to the why of the beginning being better than the end: it produces keywords that never come back up, as if there was an intention to use it differently but they either forgot or ran out of time.

In theory, past the bottleneck, there are a greater number of missions than in the beginning (11 as opposed to 9). But there is much less variety. After the 6th row, progress is linear. Even the keyword does not provide an option but moves you to a different mission. Prior to that, the bulk of the missions lead to one mission.

Not only are there fewer choices in the back half, but the choices themselves are worse. The choices in the beginning are tough. They are usually between two goods, so the agency is much more core. The choices in the back half are between bads. Oh, sure, they are meant to be much harder, as they have much more moral dimensions, but as is in line with karma systems in video games, the evil choices are lousy. My general thought was ‘why would I ever do that?’ Not ethically, but functionally.

The problem is the “Same Six Mechs” problem, to some extent. In theory, the result of the immoral choice ought to be less game. The intention is that you are taking an out, doing something sketchy that gives you an edge. Only the edge isn’t. The fights are easier. But just not enough easier, and the whole result is that, in effect, you’re getting less game.

Also, and I cannot prove this, but I believe that another bit of evidence for the unfinished business quality of the back half is in how I think that one of the choices is meant as a moral choice. There are aspects of the mission design in comparison to one another that only make sense to me if there was meant to be a further set of effects there in the mix.

This, then, explains the X. I played three times, with three different teams. The first time I played all the way through. The second time I noted where things were heading in the back half, so stopped early. The third time was more self-constructed, building my own flowchart to pick up on missions I would miss otherwise and wanted to play.

Good Ol’ TL; DR:

I made the comment in my preview that Scouring Sands felt neither here nor there based on when it was set. I reaffirm that. If you are more on the role-play side, it satisfies for play but the lack of story responsiveness is going to end things on a downbeat. If you are more on the gameplay side, the scenarios are good, but the competent but not capable automated opponent is going to feel light (though maybe advanced difficulty helps). Maybe you come out ahead if you like the arts and crafts the most. Either way it’s a buffet. Something for everyone, but no one thing of renown.

Leave a comment